[First published in Mint Print Edition, 17th May 2024.]

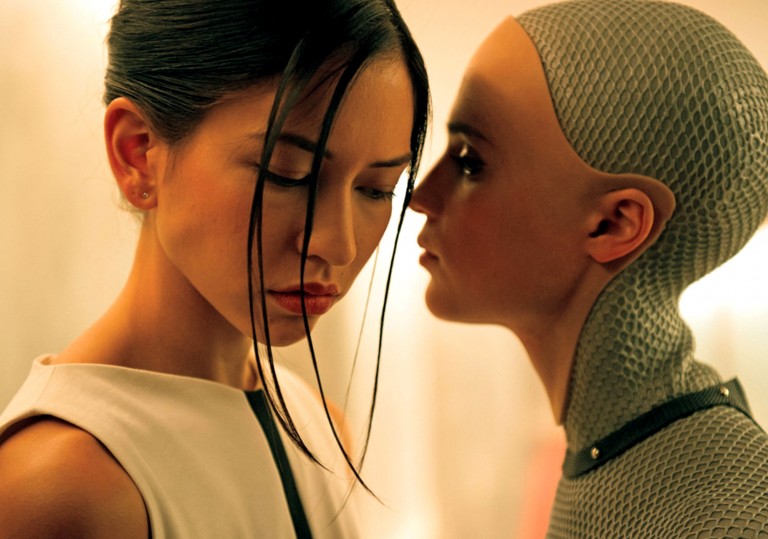

“To erase the line between man and machine is to obscure the line between men and gods,” says the line in the teaser clip for the movie Ex-Machina released in 2015.

What technology does for us has never been a topic for a discussion or debate. But in the last decade or so, ever since social media became central to our lives, the question “what does technology do to us?” is a matter of profound interest. Even more now, in the last few years, after the conversations on AI have become mainstream.

Making machines that behave like, or at least closely resemble, human beings, has been a pursuit for over the last 200 years or so. As early as in 1800s, Austro-Hungarian inventor, Wolfgang von Kempelen tried making a Speaking Machine using bellows and reeds to model human vocal tract. This was later improved by Sir Charles Wheatstone, which in turn influenced Alexander Graham Bell who tried creating his own device. (While Bell’s speaking machine didn’t materialise, it helped the invention of telephone.) The first electronic talking machine ‘Voder,’ was created by Bell Labs and exhibited at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. In the 1950s, efforts began by early AI pioneers for speech recognition (which did not mean speech understanding).

Decades and many breakthroughs later, we are in throes of a man–machine interaction revolution. But what does it do to us?

Our interactions with ‘intelligent’ machines is not just about those machines. It is also about us. When we interact with machines that responds human like, what does it do to us, our perceptions, emotions, and our neural wirings ? Much is not known, except that it is changing us. Just like human-to-human interactions are triggering our neurons, making biochemical changes, and altering our bodies, so are human to machine interactions. Even as we get into these interactions with the full knowledge and awareness that they are machines, we are perhaps slowly becoming ‘in communion’ with these machines.

The first chatbot came much before the internet became mainstream. An MIT professor and computer scientist, Joseph Weizenbaum, built ELIZA in 1966 as a conversational interface between humans and machines. ELIZA engaged with users like a psychotherapist and most people started attributing human-like feelings to the program, wanting to share intimate matters and spending time alone with the machine.

Artificial Intelligence is now touted as the solution for loneliness, as a companion. Crossing the chasm from the ability to understand (conversational applications so far) and the ability to care. (Is there a Turing Test for empathy is the new question.)

A recent study by Sherry Turkle at MIT, “Who Do We Become When We Talk to Machines?” 1 delves deep into the impact of human–machine conversations. Turkle is an American sociologist, trained psychologist, a professor at MIT, and the author of some of the acclaimed books like The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit and Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other. (Turkle also taught at MIT along with Joseph Weizenbaum and studied people’s interaction with ELIZA, terming the emotional engagement ELIZA Effect.)

The study explores “how our digital relationships affect our understanding of human connections” and is also an attempt to develop methodologies that study how artificial empathy changes our relational capacity. Turkle coins an interesting term—Artificial Intimacy (AI). The study had people from wide range of backgrounds and demographics as its participants–young PhD pursuers to social scientists to IT professionals. The research subjects were either users of AI-based conversational tools, such as Replika, Pi, Woebot, and ChatGPT, or users who were newly introduced to these tools. As they use the tools, people were found to be experiencing an emotional bond with the technologies they are engaging with.

The results of this study raises some of the pointers that might have far-reaching societal impacts, and perhaps even the evolution of our species.

One, most or all participants find it very relieving to deal with machines than humans, because it replaces “stressful human connections.” Real relationships have more friction and is difficult to deal with. Talking to machines make them feel less vulnerable, no friction, no second guessing and no fear of being left behind. The machine friend (or companion) legitimises, and gives validation. But doesn’t not getting wired to deal with real people and real experiences make us more emotionally fragile? As Turkle notes, “If we live in a culture where significant numbers of people say they should never have to be made uncomfortable, and since discomfort, disappointment, and challenges are part of most human relationships, that is a dilemma.”

Second is the argument that AI built on collective intelligence of many experts is better than any single expert. Eric Schmidt, former Chairman of Google is quoted as saying that Generative AI will make “much of human conversations unnecessary.” But Turkle asks the most important question, “When we are in human conversation, we often care less about the information an utterance transfers than its tone and emotional intent. In a world that deals in averages, what happens to our sensitivity to all this?”

What does all this mean to us? What does it mean to be human? Is being human a relative term? Will we now be engineered by machines? Are we being shaped by past data or laws of averages? Will we get more standardised and homogenised?

More questions. Few answers.

- Reference

Turkle, S. (2024). Who do we become when we talk to machines? An MIT Exploration of Generative AI. https://doi.org/10.21428/e4baedd9.caa10d84 ↩︎

More on Sherry Turkle and her work.