“Can a history of interest rates really entertain? You bet.. To read this terrific book is to be reacquainted with the bizzaire, Alice-in-Wonderland condition of modern finance” – Marc Sidwell, Sunday Telgraph. [From the blurb on the back cover]

I have been reading books on economics of all types for the last many years, as part of the efforts to understand how the world works. But I must admit that I find it difficult even now to understand many aspects of economics. Economics is supposedly said to be the ‘dismal science’, while the origins of this statement are still contested. It is perhaps true that economists often go wrong because the real world works irrationally, while economists believe that all human beings think rationally. A comparison between science and economics goes like this – “(in science) With every refinement and creation of new models, science becomes closer to reality. But Economics move away from reality.” [I am not able to recollect the source of this quote]

The last book I finished very recently is “The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest”, by Edward Chancellor. After reading the blurb, the reviews, a few inside pages and a battle in my head (whether this will become yet another unread book in my anti-library), I picked it up from the shelves.

The Price of Time is an interesting book about ‘interest’ and therefore money and economics. The key premise is that deliberately creating lower interest rates always hurts the economy. The book takes us through the historical origins of interest during the Babylonian times, the mediaeval times, pre-modern and modern times, and the present times. It traverses the many social contexts, the story of many bubbles, and the aftermath of the 2008 crisis.

History suggests that interest has been part of human transactions and early inscriptions (in tablets) show how these transactions were recorded. ‘Interest’ in early civilisation also emerged from the lack of capital. But ‘Interest’ as a sin, lazy money, usury, undeserving etc have been a predominant narrative during most of history. The word ‘usury’ comes from the Latin word ‘usuarius’ which means ‘one who has the use but not ownership of a thing’. At some point in the early modern era, interest in consumption loans was seen in a negative light, while interest in productive capital loans was acceptable.

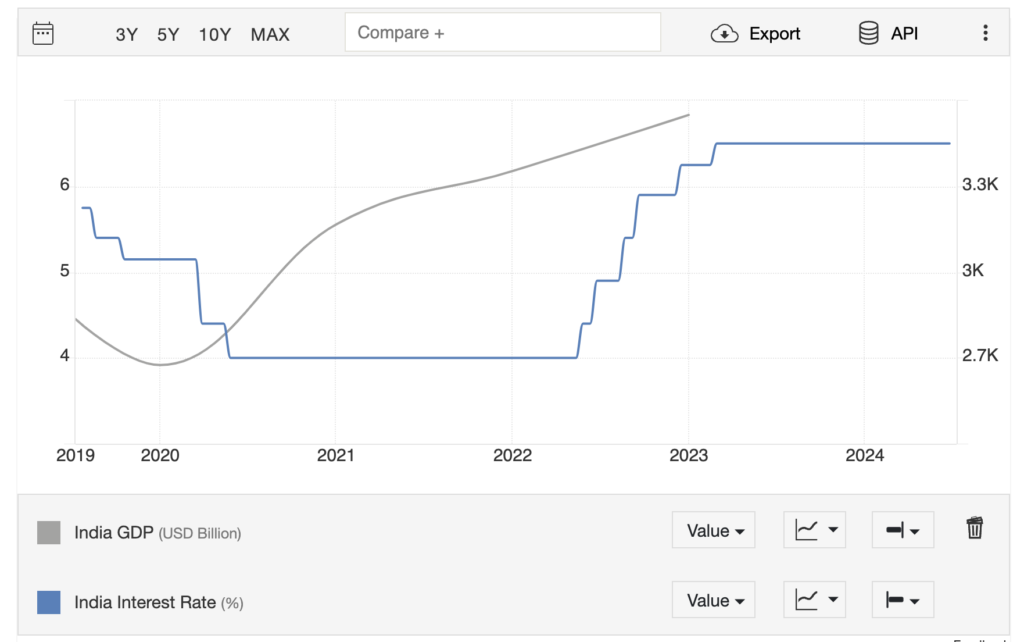

Rich in many historical curiosities, discourses and debates, the book is an enjoyable read. Apart from the curiosities, some of the many new things I was exposed to include the fact that there is no correlation between interest rates and economic growth, the question that ‘is there a natural rate of interest’, how globalisation and flow of capital impact interest rates (which I didn’t understand well) etc. The historical titbits also include that the origin of the word ‘capital’ is from ‘caput’ – a head of cattle!

The book is in three sections. Part 1 covers the historic context, starting from the Ancient Near East through the Middle Ages to the birth of capitalism in Europe. Part 2 looks at the unintended consequences of monetary policies driving low interest rates with stories from different markets. Part 3 covers the impact of low interest rates in emerging markets including Brazil, Turkey, and China. The China story is detailed with a separate long chapter on China.

What is abundantly clear is how deliberately low interests make money easily accessible for people who don’t need it really and only end up helping corporations do share buy-backs, overheating the street, and giving rise to all types of bubbles.

While I was sceptical about my ability to comprehend and complete the book, Edward Chancellor’s lucid and easy style made it easy. And it did put some pieces together in the large complex puzzle of interpreting the world.